Post-apocalyptic Musings

- By Koji Mukai

- January 3, 2013

- Comments Off on Post-apocalyptic Musings

Congratulations! You have survived the end of the world on December 21st, 2012. Many of you who never believed it may nevertheless be relieved, thinking that we can now forget about these apocalyptic prophecies. But, you would be wrong, in my opinion. It’s likely that, before too long, the Internet will be abuzz with new or recycled prophecies of doom. In fact, I don’t think these doomsday predictions are newsworthy, and should largely be ignored, because the end of the world happens so frequently. It does, that is, if you believe everything you read online. There is even a handy list on Wikipedia.

Maybe many rational people enjoy these fantastic scares, the same way many people enjoy horror movies, simply as escapist fun. I, too, enjoyed reading about Nostradamus’s supposed predictions as a young boy. Then there are people who are trying to make money – well, it’s a free country. For example, I don’t resent Hollywood for making the movie 2012, although I think there is much to criticize in a viral ad campaign for that movie. For this, the studio created a non-profit sounding website while effectively hiding any affiliation with the movie. I pity the people who thought that website was for real.

Anyway, I thought this might be a good time to make a few general points related to some of these doomsday scenarios, now that one specific, well-publicized end-of-the-world prediction is behind us.

(1) Do we live in a dangerous universe?

Yes, definitely. But nothing has destroyed the Earth for over 4 billion years, and it’s been about 65 million years since the global extinction that killed off the dinosaurs. Many of the things that disaster prophecies mention – alignments of planets, for example – happen far more frequently than that, without any ill effects. If the human civilization can prosper for millions of years, then we may have to worry about space-based threats to the very existence of our race; over much shorter time frame (centuries, or even millennia), the chances of such huge catastrophes are almost negligible.

Toutatis is an asteroid with an orbit that puts it close enough to Earth to be considered a potentially hazardous object. Scientists believe it poses no real threat, and on December 12, 2012 it passed within 18 lunar distances to Earth.

Credit: NASA’s Deep Space Network antenna in Goldstone

We should, nevertheless, worry about lesser but significant dangers from space – say the equivalent of magnitude 9 earthquakes or category 5 hurricanes. Specifically, we need to worry the most about impacts by comets or asteroids, given what we know of various cosmic dangers. For the last 15 years or so, we have made significant investments of resources to try to discover as many potentially hazardous objects in the Solar system, and none that poses an immediate danger has been found. Smaller objects are harder to discover, and they are more commonplace. One could still strike us with little warning, and cause huge (but far from civilization ending) damage. Our ability to spot potential dangers is improving, people have thought about how one might deal with such objects if found, and we should continue to invest in these areas. Rest assured, also, that scientists are happy and eager to study any other potential dangers out there.

Meteor Crater, Arizona. Credit: Maggie Masetti

(2) Is NASA hiding information about a potential disaster?

For those of you who are not laughing at the very idea that NASA would want to, or can, keep such a secret: No.

For one thing, data obtained with NASA missions belong to the public. Some data have a proprietary period, but they are all made public sooner or later (later usually means 1 year from when they are taken). Anybody can look at the data and draw their own conclusions.

More importantly, though, NASA has no monopoly on observations of the solar system and beyond – for every observation made with a spacecraft, many more are done at ground-based observatories. Moreover, many amateur sky-gazers monitor the sky all the time. Since the professional telescopes usually cover only a very small patch of the sky at any given time, amateurs (many of them far from amateurish) make important contributions by discovering many comets, novae, and supernovae, for example. Also, professional astronomers rely on an army of amateurs to monitor hundreds of variable stars night after night for month, years, and even decades – SS Cyg is a famous example of this. If there is a dangerous object in the sky, amateur astronomers may well discover them first – and any efforts by NASA to try to keep it secret would be futile in such a case.

(3) Did ancient civilizations know something we don’t?

To state the obvious, we have better telescopes and instruments that no ancients had. Still, observations made centuries ago can make important contributions to astronomy, similar to the way amateur astronomers do. However, in many instances, ancient texts are useless because they are not precise enough for scientific purposes. Are we translating the ancient text correctly? Was a particular passage in an ancient text meant literally or figuratively? If you think the text said the star was shimmering, how do you interpret this?

Ancient Observatory, Beijing China.

Credit: Maggie Masetti

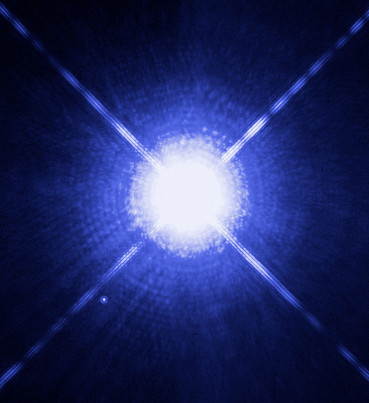

Here is an strange case of the color of Sirius, which is an A-type star with a brilliant white color. However, many Greek records say Sirius was a red star. Astronomers have had fun speculating how Sirius could have changed color in 2,000 years, but the answer appears to be cultural. As I mentioned in a previous blog, Egyptians and Greeks most intensely observed the heliacal rising as a marker of the passing seasons. For this purpose, they observed Sirius when it was close to the horizon, where stars can look quite red. A strong evidence for this interpretation is that the Chinese records always described Sirius as white. Note that in China, the heliacal rising of Sirius was not used as a seasonal marker. This means sometimes you have to know the cultural context as well, even when you are reading the ancient text correctly.

Hubble Space Telescope image of Sirius A and B. It is overexposed so the smaller body can be seen.

Credit: H. Bond (STScI) and M. Barstow (University of Leicester)

Those who use ancient text as basis for predicting an upcoming disaster are sure that their particular reading is correct, even when mainstream specialists in the field dismiss such an interpretation. In the case of the Mayan prophecy, we all know which camp was correct.

If you have made it all the way through my musings, I hope you are a little better prepared for the next Internet rumor of imminent doom.