Celebrating GALEX

- By Maggie Masetti

- August 2, 2013

- 1 Comment

We recently said a fond farewell to the Galaxy Evolution Explorer (GALEX) mission, which was decommissioned in June. GALEX had a single instrument onboard that was both an imager and a spectrometer at UV wavelengths. It was launched in April of 2003, and spent 10 years studying hundreds of millions of galaxies across 10 billion years of cosmic time.

So, do non-visible light missions take pictures as beautiful as those taken by Hubble? I think you’ll be pleasantly surprised by the gorgeous ultraviolet images captured by GALEX, which are just as lovely as those taken by the visible-light (and more powerful) Hubble.

Additionally, multiwavelength astronomy is a powerful tool. Each wavelength can reveal something new and different about the object you are observing. For example, infrared light is valuable because the earliest galaxies are only visible at that wavelength due to the expansion of the universe, which is causing the light these galaxies emit to shift to redder wavelengths. Additionally, stars are born in dusty cocoons of gas that are opaque to visible light. But infrared wavelengths emitted by these baby stars are visible through the dust, so new stars and planetary systems are often best studied in the IR. As for the ultraviolet, most stars are too cool to emit light at this wavelength – but there are exceptions. Young massive stars (and some very old stars), nebulae, white dwarfs, and things like active galaxies and quasars shine brightly in the UV, allowing these objects to be highlighted in images of galaxies and nebulae.

Here are a few examples of GALEX observations; a few of them are multiwavelength:

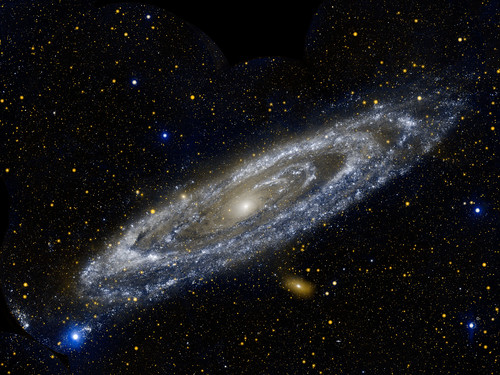

M-31, Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Hot stars burn brightly in the above GALEX image, showing the ultraviolet side of a familiar face. At approximately 2.5 million light-years away, the Andromeda galaxy, or M31, is our Milky Way’s largest galactic neighbor. The entire galaxy spans 260,000 light-years across – a distance so large, it took 11 different image segments stitched together to produce this view of the galaxy next door. The bands of blue-white making up the galaxy’s striking rings are neighborhoods that harbor hot, young, massive stars. Dark blue-grey lanes of cooler dust show up starkly against these bright rings, tracing the regions where star formation is currently taking place in dense cloudy cocoons. Eventually, these dusty lanes will be blown away by strong stellar winds, as the forming stars ignite nuclear fusion in their cores. Meanwhile, the central orange-white ball reveals a congregation of cooler, old stars that formed long ago. When observed in visible light, Andromeda’s rings look more like spiral arms. The ultraviolet view shows that these arms more closely resemble the ring-like structure previously observed in infrared wavelengths with NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope. Astronomers using Spitzer interpreted these rings as evidence that the galaxy was involved in a direct collision with its neighbor, M32, more than 200 million years ago. Andromeda is so bright and close to us that it is one of only ten galaxies that can be spotted from Earth with the naked eye. This view is two-color composite, where blue represents far-ultraviolet light, and orange is near-ultraviolet light.

NGC 6744, Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

This image from GALEX shows NGC 6744, one of the galaxies most similar to our Milky Way in the local universe. This ultraviolet view highlights the vast extent of the fluffy spiral arms, and demonstrates that star formation can occur in the outer regions of galaxies. The galaxy is situated in the constellation of Pavo at a distance of about 30 million light-years. NGC 6744 is bigger than the Milky Way, with a disk stretching 175,000 light-years across. A small, distorted companion galaxy is located nearby, which is similar to our galaxy’s Large Magellanic Cloud. This companion, called NGC 6744A, can be seen as a blob in the main galaxy’s outer arm, at upper right.

CW Leo, Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

A runaway star, plowing through the depths of space and piling up interstellar material before it, can be seen in this ultraviolet image from GALEX. The star, called CW Leo, is hurtling through space at about 204,000 miles per hour (91 kilometers per second), or roughly 265 times the speed of sound on Earth. It is shedding its own atmosphere to form a sooty shell of discarded material. This shell can be seen in the center of this image as a bright circular blob. CW Leo is moving from right to left in this image. It is traveling so quickly through the surrounding material that it has formed a semi-circular bow shock in front of itself, like a boat moving through water. This bow shock is made of superheated gas, which flows around the star and is left behind in its turbulent wake. This blown-out bubble is 2.7 light-years across, which is more than half the distance from our sun to the nearest star, or 2,100 times the size of Pluto’s orbit. The size of the bubble (called the “astrosheath”) has allowed astronomers to estimate that CW Leo has been shedding its atmosphere for about 70,000 years. This is part of the star’s natural life cycle as it runs out of hydrogen fuel and gradually throws off its outer layers to expose its bare, dying core. This core is called a white dwarf, and is the end product of all low-mass stars like our sun. CW Leo is the second runaway star to be observed with the Galaxy Evolution Explorer. The first, Mira, was observed by the telescope back in 2006. This image is the combination of near-ultraviolet data, shown in yellow, and far-ultraviolet data, shown in blue.

Cartwheel Galaxy, Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

This image of the Cartwheel galaxy shows a rainbow of multi-wavelength observations from NASA missions, including GALEX (blue), the Hubble Space Telescope (green), the Spitzer Space Telescope (red) and the Chandra X-ray Observatory (purple).

Helix Nebula, Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

This is the Helix nebula, as seen in ultraviolet light by GALEX. It is a star like our sun but at the very end of its life. The star is a small dot in the center, surrounded by billowy layers of expelled material.

Mira A, Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

A speeding star (Mira A) can be seen leaving an enormous trail in this image from GALEX. Nothing like this stellar “tail” had even been seen before at the time the telescope spotted it. The tail stretches across 13 light-years of space. Intern Jason McCracken actually blogged about this image!

Cygnus Loop Nebula, Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Wispy tendrils of hot dust and gas glow brightly in this ultraviolet image of the Cygnus Loop nebula, taken by GALEX. The nebula lies about 1,500 light-years away, and is a supernova remnant, left over from a massive stellar explosion that occurred between 5,000 to 8,000 years ago. The Cygnus Loop extends over three times the size of the full moon in the night sky, and is tucked next to one of the “swan’s wings” in the constellation of Cygnus. The filaments of gas and dust visible here in ultraviolet light were heated by the shockwave from the supernova, which is still spreading outward from the original explosion. The original supernova would have been bright enough to be seen clearly from Earth with the naked eye.

Images and captions are from this set on NASA.gov. Please also visit the GALEX website for a larger image gallery as well as news releases and other information about the mission.

Outstanding description of the complexity of the universe!!