Finding Herschel

- By Maggie Masetti

- July 1, 2013

- 1 Comment

We have an extra-special guest blog today! Nick Howes of the Faulkes Telescope Project wrote a blog for us about about his recent mission to find and image a legendary European Telescope.

There are only a few years to go before the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope, which will wind its way out to the Lagrange 2 point and observe the Universe in unparalleled detail at infrared wavelengths. I decided to test out an experiment to prepare for future observations of JWST from the ground as it makes its way out to this stable orbital position, and also when it arrives. The experiment was an attempt to first observe the Herschel Space Observatory, which recently departed from its orbit at L2.

A sense of urgency crept up on me and my team after we’d read online that the JPL Horizons system would not be able to provide any more coordinate data for recently-decommissioned Herschel, currently the largest single mirror telescope ever put into space. We also noticed that the Minor Planet Centre coordinates and the JPL ones were some way out from each other, a big problem when trying to narrow down the orbit on any object.

The Herschel Space Observatory

Herschel launched from an Ariane rocket (similar to that which will launch the JWST) in 2009, alongside the Planck satellite. In April 2013, the coolant had run out on Herschel, so the ESA flight team decided to test some in-orbit functions and then place the spacecraft into a so called “graveyard orbit” around the Sun.

With the coordinates from JPL showing its position rapidly running out, and the spacecraft communication severed, where would it end up? For example, the location of many of the Apollo remnants is unknown, some of which have quite recently been mis-classified as asteroids, and that was something we didn’t want to see happen here. So myself and my Italian colleague Ernesto Guido, who I work with over the internet on comet and asteroid observations, took it upon ourselves, literally at the last moment, to try to image and help get some solid orbital data for Herschel before she was lost forever.

We were lucky that the 2-metre, almost Hubble-sized telescopes we used, the Faulkes Telescopes (one in Hawaii and one in Siding Spring, Australia), both had views of where Herschel should be… I say “should be” as the coordinates from the superb Minor Planet Centre and those from the equally superb JPL Horizons team were, as I say, different, and by quite a margin, given we were looking at such a narrow piece of sky with our cameras.

Still, we love a challenge, so we booked 2 hours in total over two days in an attempt to find it, image it and get real scientific coordinate data on it. On the first set of observations, we managed to reach down to a respectable magnitude 20 (our record is magnitude 23.5 with good seeing) in a matter of two minutes. With seven images taken, tension was mounting at our respective offices. Would Herschel be in the images?

We used some off-the-shelf stacking software called Astrometrica (which is a staple for comet and asteroid hunters and imagers), and low and behold, pretty close to where JPL thought it was (but still out from, something later explained to us by ESA engineers as possibly being a result of the orbital burn data not yet reaching JPL’s ephemeris team), was an object, about the right kind of magnitude, with the right motion through the sky in the right direction. But still we had to wait.

With good science, you have to support your work, and we knew that if we were to prove it was indeed Herschel, we’d have to image it again. So we booked 2 more hours, just to make sure, and thankfully this extra gamble paid off!

The next day the telescope in Siding Spring was completely rained off, so we knew we had just one shot at this – to get it in the hour we had on the scope in Hawaii. We also knew the coordinates were off, even against the JPL data. We took two sets of images in two fields, the first based on our calculations and then slightly closer to the JPL ones…

After a very tense 30 minutes of blinking the images, looking for anything moving, and then stacking the images again, we found it, almost exactly where we thought it may be in the JPL-inspired field (though still off, but off by the same not inconsiderable margin from their positional data).

By this point, ESA staff were helping us with information on the rotation of the spacecraft (which may affect the magnitude/how bright it was) and other very useful data.

One of the happiest emails I’d seen that day was a wistful “sigh” from an ESA engineer who was utterly delighted to get one last look at the spacecraft he’d helped to manage for years.

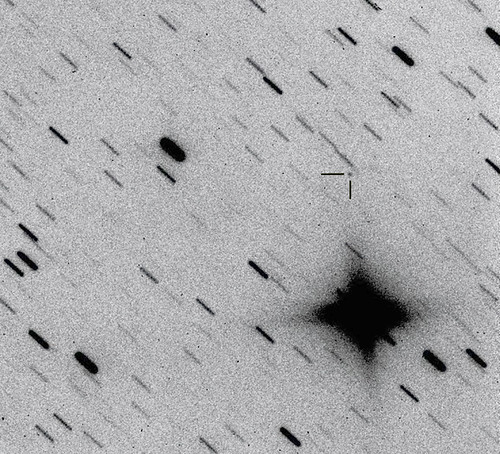

So, here’s the image – this tiny dot against the streaking star field is one of the last views that ground-based observers will be seeing of the iconic Herschel Space Observatory for some time. Over the coming weeks we’ll be refining the orbital data more, and collaborating with major observatories around the world, such as Kitt Peak and the CTIO in Chile. The communications with the ESA flight team and our friends at these observatories have shown the power of collaboration in science, and how the amateur astronomy community can really provide solid input in to professional areas.

In 2018, we’ll be aiming our scopes at the JWST, getting students to take observations, and play a part in what promises to be the most iconic telescope of the next generation. And at some point, in a decade or so from now, Herschel will return to our neck of the celestial woods, hopefully to be imaged again, safe in the knowledge that nobody will ever mistake her stark beauty for an asteroid.

Images taken and processed by N.Howes and E.Guido with Faulkes Telescope North which is operated by Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope Network

About the Faulkes Telescope:

The Faulkes Telescope, based at the University of South Wales in the UK is an educational project which Nick Howes manages pro-amateur collaborations for, and is aimed at providing school students access to research grade telescopes. Through 2014 and 2015, Howes and his team will be providing ground support for ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft as it approaches comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, using the two Faulkes Telescopes.

Nick and his team are also working currently with both the Planetary Science Institute and the Space Science Institute in the United States, on long-term comet observation projects.

The image was taken by N.Howes and Ernesto Guido using Faulkes Telescope North in Haleakala, Hawaii. The Faulkes Telescopes are operated by the Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope Network.

Great work Nick and Ernesto. There must be dozens of other objects like this that need recovering/refining. Can’t wait for the JWST to finally lift off.