How To Kill A Dinosaur From Space

- By Faith Tucker

- August 11, 2010

- 3 Comments

Go ahead and take a moment to think back to those blissful years of childhood, all those mandatory naps and the impish grins that let you get away with anything. Ah, the good old days. Well, I’m willing to venture a guess that right about the time that the sand box constituted your primary social networking site, you were already dreaming big for the rest of your life. For many of us, that meant honing our (cardboard) spaceship flying skills for the day when NASA would call on us for some daring new feat of space exploration. But some children’s dreams strayed in other directions, perhaps toward those goliaths of ancient history, those part bird/part reptile/part dragon creatures, and the inspiration for countless movies from “The Land Before Time” to “Jurassic Park” — dinosaurs! But what do dinos have to do with astronomy, you ask? Well, let me tell you.

An Iguanodon at the Royal Belgian National Institute of Natural Science

An Iguanodon at the Royal Belgian National Institute of Natural Science

Once upon a time, over four and a half billion years ago, there was a cloud of interstellar dust and hydrogen gas drifting listlessly through the innocuous outskirts of the Milky Way galaxy. That mysterious agent of the universe we know as gravity began working its magic, and soon our humble cloud had condensed into a tightly packed, boiling, churning proto-star. It became so intensely hot in the bowels of our young Sun that protons were compelled to quantum tunnel right through that Coulomb Barrier that kept them from their similarly charged proton comrades, and just like that fusion had begun, thrusting the Sun into stardom.

As the protons were doing their thing in core of the Sun, the tiny particles of dust and ice swirling around the outside of our young star also became acquainted with each other. Casual meet and greets (Mr. Dust Particle, meet Ms. Ice Particle…) turned into raging discos of jump-jive-and-wailing matter, and before you know it, four terrestrial planets had formed and were tearing their way around the Sun. And, as you are (hopefully) well aware, one of these budding planetesimals was our very own Earth.

Baby dinosaurs at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Science

Baby dinosaurs at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Science

And then a whole lot of messy geology and biology later… enter the dinosaurs. These mysterious critters — some mammoth and some not much larger than your neighbor’s terrier, some bumbling leaf-eating herbivores and some bearing slightly sharper teeth — have captured the imagination of more than a few homework-plagued, daydreaming youths over the years. But whatever happened to our Jurassic Park friends?

A Tyrannosaurus Rex at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Science

A Tyrannosaurus Rex at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Science

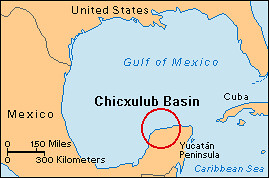

This is where astronomy comes in. 65.5 million years ago, while T-rex and his buddies were minding their own business and devouring everything in sight, a solitary asteroid was plodding along its fateful path, heading straight for earth. This asteroid, with a diameter of 10-17 km, set its sights on Chicxulub (pronounced chik-su-loob) on the Yucatan Peninsula of current day Mexico and let gravity do the rest.

The Chicxulub impact crater on the coast of Mexico, Photo Credit: NASA

An artist impression of a massive impact, Photo Credit: NASA Goddard

The inevitable collision not only left a gaping hole in our planet spanning 25,000-30,000 square kilometers (with a diameter of 180-200 km), but the impact released huge amounts of climatically sensitive gases and one enormous debris cloud into the atmosphere. You thought Eyjafjallajokull’s ash cloud this April was big, check this out: rocks, dust and gas were violently ejected at speeds of a few km per second and quickly covered the entire globe’s surface with a layer between 100 m and 2 mm thick (depending on distance from the impact site)! But that kind of cataclysmic event is bound to do more then just kick up some dust. An extended period of darkness enveloped the Earth as acid rain showered down sulfur, earthquakes of 11+ magnitudes rattled the mountains, global temperatures dropped dramatically, widespread tsunamis swept away helpless landlubbing creatures and 75% of the world’s species were wiped clear off the Earth, including the dinosaurs.

(For a great solar system timeline, check this out!)

No, unfortunately I did not go visit the Chicxulub crater, most of it is buried under the Gulf of Mexico, anyways. But I did do something almost as cool…

As I walked into the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels, home to Europe’s largest dinosaur gallery, I was immediately surrounded by a herd of Iguanodons and a towering Tyrannosaurus Rex. But despite the imposing company, my eyes were drawn to the small display in the far corner of the exhibit, resting on top of which sat a rock about 3 ft across. Being good friends with a number of geology majors has taught me that rocks are often much more interesting than they appear, so I decided to give this one a chance. As I approached, I read the label that said, “A part of the Chicxulub asteroid that caused the extinction of the dinosaurs.” What!? A giddy wave of astronomy nerdiness surged up in me as I peaked over my shoulder to see if any curators were nearby and then reached out my hand and touched the infamous and deadly space rock. I have never in my life been so excited to touch a rock as I was at that moment.

A small hunk of the Chicxulub asteroid!

From that moment on, my deep comradery with dinosaurs was cemented for life. You may not find a toy chest full of dino figurines in my room, nor will I ever travel the world digging up dinosaur bones; but I touched part of the asteroid that ended their reign of this planet, and that makes them very special to me indeed.

Another dinosaur from the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Science

*Note: Thankfully, the likelihood today of a surprise attack by a catastrophic asteroid collision is practically zero thanks to NASA’s Near Earth Object (NEO) Program that monitors and tracks all objects that might swing by close to Earth. I can’t tell you what we’ll do when we do find another small country hurtling toward us like the dinosaurs did, but at least we have time to think about it since nothing seems to be heading directly our way in the 21st century.

The head of an Iguanodon at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Science

Pacific ocean? Or the Caribbean?

The impact is thought to be centered near Merida, Mexico on the Yucatan Peninsula on the Gulf of Mexico/Caribbean side.

[…] top of this, there are also tangentially relevant blog posts, such as this one from NASA Goddard’s Blueshift Blog, which describes a researcher’s delight at touching […]