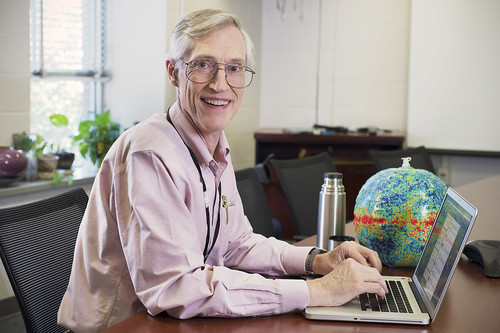

A Conversation with John Mather

- By Maggie Masetti

- January 20, 2016

- Comments Off on A Conversation with John Mather

You might recall our recent interns from Germany, Daniela and Verena, who guest blogged for us a few times. They did some interviews with people working on the James Webb Space Telescope while they were here and we thought we would share this one with Nobel Laureate and James Webb Space Telescope senior project scientist. Enjoy! -Maggie

October 31st, 1995: The “Next Generation Space Telescope” (NGST) project, now known as “James Webb Space Telescope” (JWST) starts to become a reality. Twenty years later we’re sitting together with Dr. John Mather, Senior Project Scientist at Goddard and one of the Founders of JWST. Working at NASA for over 40 years provides a lot of experiences and stories.

Artist’s Impression of the James Webb Space Telescope, Credit: Northrop Grumman

Daniela and Verena: How would you describe your areas of activity to a layperson?

John Mather: Oh, to a layman it would look like I just sit and talk and write e-mails. But I guess, the more interesting thing is what the conversation is about. So the conversation is about ‘What do we need to do?’ so that the telescope will work. And so some days it’s about the engineers and technicians that found something that isn’t quite right, so ‘What are we going to do about it?’. Some days it is just making sure that the scientific world is ready. So we talk to our scientists around the world to say ‘This is how we’re going to operate the telescope. This is what you have to do to prepare a proposal.’ If you’re a scientist then you find your friends and you say ‘This is the topic I think we really should examine and then this is how much time we need from the telescope to answer our questions. This is why we’re the best team in the entire world to do this work.’ Afterwards, a committee will consider the proposals. We receive thousands of proposals – it’s a very popular telescope. So that’s what our conversations are about these days. A time ago, it was more about how could you possibly come up with a technology that would enable such a telescope. Because at the beginning none of this was possible – it was only an idea. So we needed mirrors and detectors and we needed to make an agreement amongst various space agencies about who was going to do what. All of those things were very tricky and they showed us what things to do.

Credit: NASA/Chris Gunn

Daniela and Verena: What was your favorite moment at the JWST project so far?

John Mather: It’s hard to say. I think my favorite moment will be when it goes up and successfully reaches orbit, unfolds in space and functions properly. That’s the thing everyone thinks about.

Daniela and Verena: The JWST is a very complex construction project. In your eyes, what is its biggest challenge?

John Mather: I think everyone believes that the biggest challenge is to make sure that it unfolds properly in space. Because this is new – that is not something we’ve done many times. Many observatories have things that unfold in space but ours is much more precise for the unfolding. So it’s complicated and has this big sunshield design – nobody ever needed a piece of plastic as big as a tennis court in space. It all has to be carefully designed, managed and tested. We also have to imagine every possible way to go wrong and then make sure that this does not happen. So it’s either by thinking about it or by designing something or by testing something that you have to succeed in making a good design. Then, at the very end, of course it’s the technicians, the people who actually touch the equipment, that have to do their job exactly right.

Daniela and Verena: Winning the Nobel Prize is for sure an experience with far-reaching effects. Can you tell us if it resulted in any professional or private changes?

John Mather: I think the main changes were getting far more invitations for traveling and speaking. I tried to make no other changes – I have the same job that I had beforehand. The prize came in 2006 and the telescope project was already eleven years old by then. So I’m still doing the same job and I just get more chances to talk to people.

Daniela and Verena: We know that you’re a passionate traveler. What was your most impressive destination or trip?

John Mather: I guess there are several. The most spectacular one was traveling to see the giant animals in Southern Africa – we went to Namibia and Botswana and we saw the lions and the elephants. Just thinking about the history where human beings come from and how we must have lived with lions everywhere back then – it sort of makes you think a lot. Because our history here on earth is so short as human beings, we’ve only been here for a very short time and those big animals also haven’t been here that long. Lions and elephants are also just a few million years old. Earth is like 4.6 billion years old – so what was going on between the beginning and now? That’s one of the things I love to think about. Another one is our cultural history. The first time I saw Italy and just see things written on the monuments in Latin and I thought ‘I really should have studied Latin in school so I would be able to read what they said.’ That only reaches back a few thousand years of history. So that seems to be the attraction that I feel. When traveling I’m thinking of history.

Daniela and Verena: There are a lot of young people with brilliant ideas out there. Often they are not taken seriously and have struggles realizing their visions. Which advice would you give them?

John Mather: Well, I don’t know if there’s any general advice but everything is about communication. And so sharing the ideas with other people, talking with your friends ‘I’ve got this idea, would you like to help me? Or can you make a better idea?’ – all of these things are part of the process that successful ideas have. I guess it’s always an interesting question because maybe the idea is bad. But how will you find out if you don’t try to push it forward? And maybe if you start pushing it then somebody will say ‘Oh, I have a better idea, let’s do that one instead.’ So I think it’s more like choosing the direction to go in than rather saying which exact tree you’re going to reach – it’s more direction-orientated than goal-orientated. People often talk about how goals are important to us. I think it’s less important than the direction along which the goals might be. Let’s say our direction is that we want to have civilization last for a billion years – what are the things that we have to do between now and a billion years?