“Always Keep Your Sense of Wonder”

- By Maggie Masetti

- February 16, 2011

- 1 Comment

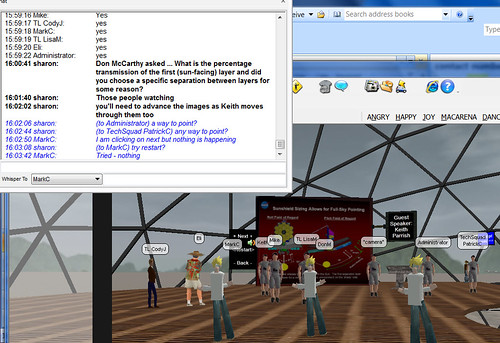

Last year I did an interview with Sharon Bowers, the teacher the James Webb Space Telescope is collaborating with on an educational engineering design challenge called “RealWorld-InWorld”. Part of this challenge (the real world part) takes place in the classroom – but the other part happens in a virtual world that is not unlike Second Life. InWorld, we now have guest speakers from the Webb project talking to the students about the challenges of working on such a complex and cutting-edge project.

The most recent speaker was Keith Parrish, an engineer at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, who manages the sunshield team for Webb. Students asked questions regarding design, engineering, and technology and were given a brief visual presentation. The event provided an opportunity for the competitors to connect with someone who is integrally attached to the James Webb Space Telescope project, and pose serious questions about advanced engineering and design.

A screenshot of Keith Parrish’s Q&A

The following is a transcript of a dialogue that transpired on February 8, 2011 after the live InWorld Q&A session with Keith Parrish. I thought you all might find it interesting. (FYI, Michael Wagner is a NASA Langley Aerospace Research Summer Scholar Intern seated at the National Institute of Aerospace (NIA). Mike is part of the RealWorld-InWorld NASA Engineering Design Challenge team.)

Wagner: You once remarked that the design decisions of a decade ago impact construction today. Care to elaborate?

Parrish: Projects that use lots of new technology, things that haven’t been flown in space or new inventions – that level of technology has to be developed, so most of the technology on JWST was developed a decade ago, or slightly before. Once you commit yourself to maturing those technologies you can start implementing them into your design. When the time comes to implement the technology it may not be exactly what you need, but you don’t always have time to keep maturing the technology before implementation. In retrospect . . . In some cases the decisions were good, in other cases we’d like to go back and make changes to design and technology.

Wagner: Tell us why you chose Kapton as the material to build the sunshield.

Parrish: Kapton is a plastic, which has some interesting properties – amber color, flexibility and its dielectric, meaning it does not conduct electricity. The orange flat ribbons in computers are usually made from Kapton. When used in space, because when you’re in space you’re in a vacuum, it doesn’t outgas a bunch of nasty chemicals, like many plastics do, which they will do on a hot day on Earth too. It’s strong and can be made in a thin rolled material – it’s like a soft structure. We looked at Kapton very early on as a possible material. We picked a specific formula that does well at cold temperatures – the specific Kapton we chose does not get brittle when cold and holds its strength – it holds coatings very well, so they can add various necessary coatings – and Kapton has lots of flight heritage.

Credit: Northrop Grumman

Wagner: Over the years have there been any valuable lessons you’ve learned, or large changes you’ve implemented?

Parrish: We’ve changed design many, many, times. We could not design the sunshield, like a lot of things are, in a computer-design environment, simply due to its flexible nature. We are in a world where we need to use models to see how things work. We knew we couldn’t do full-scale models, so we built smaller models. We also experimented with bare Kapton, meaning it wasn’t coated, which meant it was transparent, which was great for engineering data, since we could see through the shield and monitor everything on the telescope . . . however Kapton is dielectric and can build up giant static charges, so we had to coat it in order to deter the static build up.

Another thing that has surprised us, as an unintended consequence, and don’t forget this is a one shot deal, no chance to do it over . . . So, we started building in more features that would ensure that it deploys reliably . . . however the more parts you add the less reliable a machine . . . so we’ve had to balance things out, and question which parts really had to be there or not.

Regarding coating Kapton, the top layer is coated with a dope silicon material that we added metal to. The top layer, or first layer, being the sunside; we did this because the silicon reflects sun well, and the metal deters static build-up. Layers one and two are silicon coated, while layers three through five are coated with a vaporized aluminum.

Credit: Northrop Grumman

Wagner: The JWST orbits around Lagrange Point 2. At this location, should anything go wrong, it will be out of reach for repair. Which also means we can’t retrieve it when the project is over, should it ever be over. Please elaborate on this.

Parrish: As of today JWST will be about a million miles away from Earth and out of range for repair. However, nothing in the plans call for it to be repaired. Something will come along in the next few years that will be able to travel to JWST for repairs, whether that means with a human onboard, or robotically.

JWST, which orbits around Lagrange Point Two, will carry enough fuel for orbit maintenance. If it should fall out of orbit it could end up being pulled into the orbit of the Sun, or even less likely return to Earth.

NASA has a disposal requirement at the end of JWST’s useful life that ensures the telescope won’t be a hazard to human life, or other spacecraft. At the end of its mission we will point it in a direction in which it won’t be able to return to Earth and we’ll use the remaining fuel to send it that way.

Wagner: Who knows, maybe in the future someone will pick it up . . . Is there any advice or words of wisdom you’d like to offer the competitors in the RealWorld-InWorld challenge?

Parrish: I think for people entering into the fields of engineering and science some of the more practical realities of things can wear you down. It’s very easy to be excited about science and technology, but you may get a little dismayed when you come across budget matters and things like that.

I think the best words of advice that I have are “always try to keep your sense of wonder about things and that’ll compensate for the issues that you face in the field, such as money, research, etc. Remember what you love and what fascinates you. Always ask if there is a better way to do it, and if so, do it. Keep your sense of wonder about how the world operates. You know, sometimes we just take a step back and say ‘wow that’s really cool’.”

Wagner: Finally, what do you think of this virtual universe we’ve welcomed you into?

Parrish: This is really neat! It’s new for me to experience this. I think the more you can connect individuals, and at low cost, the better. This would have been really cool when I was in high school, I think I must have only met an actual scientist once and that was shadowing him for career day. This lets folks working in the fields connect with students and others of similar interests; the connectivity is amazing!

Individuals who are not affiliated with the Engineering Challenge are welcome to enter the universe as tourists and attend future events, which they may do by visiting www.niauniverse.org and downloading the application. Registration is free.

Upcoming guest-speaker events include:

- Wednesday, Feb. 23, 4-5 p.m. ET –Don McCarthy, NIR CAM Science Team

- Thursday, Feb. 24, 2-3 p.m. ET – Ray Lundquist, Systems Engineer

- Tuesday, Mar. 8, 3-4 p.m. ET – Paul Geithner, Observatory Manager

- Wednesday, Mar. 16, 4-5 p.m. ET – Michelle Thaller, Asst. Dir. – Science Communications

- Thursday, Mar. 24, 4-5 p.m. ET – Amber Straughn, Astronomer and NASA Post-doctoral Fellow

For more information about the RealWorld-InWorld Project, visit: www.nasarealworldinworld.org

Very informative article.As an architect in the Portland area I will continue to follow your progress.